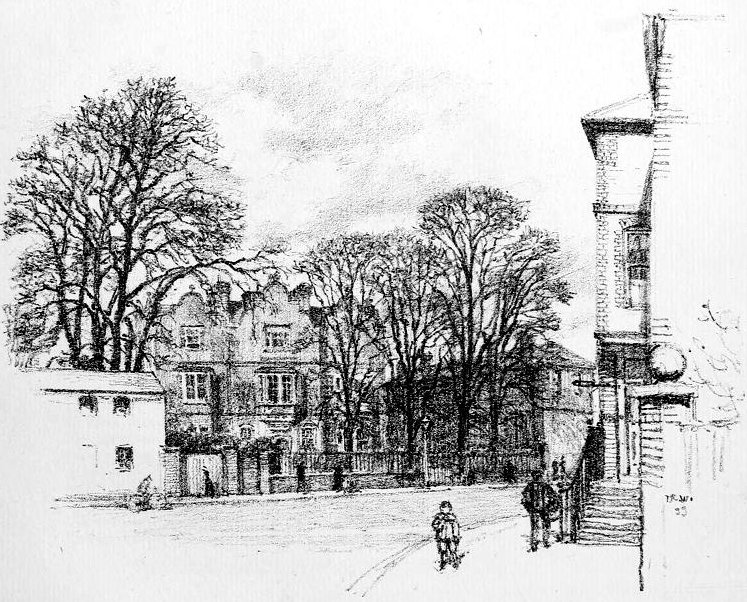

A couple of years ago I put together a few notes on the history of Wimbledon’s Eagle House – one of the few and among the finest of Jacobean manor houses which have survived into 21st century London.

At the time, I noted that in 1877 Eagle House had been purchased by one Thomas Graham Jackson (shortly before the sketch above was made) and that he put much effort into restoring Eagle House to its former glory as a home after many years in which it had been used as a school. So I was delighted today to stumble across further information about Thomas Jackson which connects him both more deeply to Wimbledon’s history but also the main theme of this blog – books!

Thomas Graham Jackson is perhaps better known as Sir Thomas Jackson (after he was awarded the baronetcy of Eagle House, Wimbledon, in the County of Surrey in February 1913). After studying at Oxford, at the age of 23 he was apprenticed to leading Victorian Gothic revival architect, Sir George Gilbert Scott, before founding his own practice in 1862 and going to become one of the foremost architects of his generation in his own right. Architect Jackson is best remembered for his work in Oxford at Oxford Military College and Oxford University (including the famous Bridge of Sighs over New College Lane and much of Brasenose college). His work and style of architecture so came to dominate Oxford that Jackson acquired the nickname Oxford Jackson and even Nickolaus Pevenser, who for the most part unsurprisingly found Jackson’s work not to his taste, conceded that once he”had set his elephantine feet” on the city it “would never be the same again” (J Sherwood and N Pevenser, The Buildings of England: Oxfordshire, London, 1974, p. 59). Jackson didn’t just bestride Oxford’s architecture though – he also worked extensively in Cambridge and on other clerical and educational buildings and the ‘Anglo-Jackson’ style became typical of many public buildings of the era.

Jackson published prolifically, producing detailed and well-researched works on architecture which often included his own sketches made during his extensive travels and a number of travelogues and memoirs. His books include one co-authored which his fellow architect, Norman Shaw, entitled Architecture – a Profession or Art (John Murray, 1892), which comprised 13 short essays on training and qualifications for architects and triggered a short retort publication by another fellow architecture, William H White, The Architect and his Artists, an Essay to Assist the Public in Considering the Question is Architecture a Profession or an Art (Spottiswoode & Company, 1892). These two publications laid the foundations for a public policy debate which was to culminate some forty years later with the passage of the Architects Registration Acts between 1931 and 1938. The Acts, which remained in force until 1997, established a statutory register of architects and restricted vernacular use of the word ‘architect’.

What sings to the hearts of both book collectors and local historians however is that later in life Jackson also penned a handful of ghost stories primarily, it is thought, to entertain his friends and family. Six (I do not know whether or not there were more) were gathered together and published in 1919 by John Murray, the same publisher who had issued some of his architectural works. The stories range in setting from 18th century London to contemporary Italy and feature both benevolent and malevolent ghosts. In ‘The Lady of Rosemount’ Jackson tells of a ghost from the past intruding into the present. ‘The Eve of St. John’ has a similar theme. ‘The Ring’ features an overly-curious traveller in Italy who is afflicted by an ancient curse and ‘Pepina’ has a restless spirit returning to haunt those responsible for its death. In ‘Romance of the Piccadilly Tube’ Jackson created one of the earliest stories of hauntings on the London Underground. It is, though, the last story in the collection that appeals most: the eponymous ‘Red House’, like Pepina featuring a returning restless spirit, is thought to be based on Eagle House, which by that time had long been Jackson’s home, and the action takes place within its confines. Jackson clearly had a deep interest in the area in which he made his home: not only did he set one of his stories in the heart of Wimbledon but he was also one of the founding members of the Wimbledon Society (then known as the John Evelyn Club). Six Ghost Stories was the only work of fiction which Jackson published but in his Recollections: The Life and Travels of a Victorian Architect he tells of a small room, an attic, in Eagle House, having “sort of hidden chamber in the hollow of the roof which in the days of the school was known as the ‘murder chamber’.” According to an anonymous article in a newsletter produced by the Wimbledon Society in 2008, ‘The Red House’ “makes great use of an identical hiding place – “a small chamber artfully hidden in the hollow of the roof’.”

At least four of these supernatural tales follow the conventions set out by the master of the genre, M R James. Indeed, Jackson acknowledges James’ mastery and influence in his preface, endorsing James’ two ‘golden rules’ of the good ghost story – that the setting must be in ordinary life, and that the ghost should be malevolent. Jackson isn’t another James but Neil Wilson, in his guide to supernatural fiction 1820-1950, Shadows in the Attic says “While Jackson’s work does not have the originality of James’ own, it does manage to combine an authentic sense of place together with a well-handled development of ghostly atmosphere and fully repays the attention of the supernatural enthusiast” (British Library, 2000, p. 278).

My inner reader yearns to devour these stories, especially The Red House, set as it is just a few yards from where I live. And the book collector in me yearns to read from an original 1919 Murray edition of Jackson’s Six Ghost Stories. They are not hard to find but are seriously and, for me prohibitively, pricey. It’s fortunate then that, although Six Ghost Stories was for decades out of print, later editions have been produced by Ashtree Press in 1999 and Leonaur in 2009 (the first with a detailed introduction by Richard Dalby and a seriously creepy dust jacket illustration by Jason Eckhardt, although even second hand either version is likely to set you back the best part of £20 (unless of course you order via your local bookshop). At the time of writing copies of a later paperback edition, with a new foreword by the well-known fantasy and science fiction writer John Grant, are available from the Museum of Wimbledon for £7.99 plus £1.25 p&p. Incidentally, the Museum’s website claims that this is the only paperback edition ever produced. I don’t believe that is entirely correct – it would seem that the 2009 Leonaur edition is available both in paperback and as a ‘collectors’ edition’ hardback. Myself? I’m going to pop along the road on Saturday afternoon and get a paperback copy from the museum while I save up for a Murray copy!

Does anyone else see some similarity between the top-hatted gentleman featured on the Ashtree dust jacket and Jackson himself? Co-incidence or design?

3 responses

As a Wimbledon resident/architectural photographer/book lover I found this article fascinating. Thank your for posting!

Thank you. And thanks for commenting too. I’m really pleased you enjoyed the post. I’m absolutely fascinated by Eagle House – I walk past it most days (shrouded at the moment) and can’t help but to wonder about the people who have lived there. When I’ve won the lottery twice, I’ll buy it!

Fingers crossed!